Supporting My Sister with Autoimmune Encephalitis: March, 2020

When It Rains It Pours: When bad things happen, and bad things often do happen, our lives must change. My sister with whom we had been celebrating my birthday on July 11, 2019 in my original home town of Calgary, Alberta, left unannounced before the end of the night from the dance club where we had been meeting. We thought it was odd that both she and my parents left without telling us. She later left a slurred voicemail message in explanation. I tried calling her back encouraging her to go to the hospital given that it sounded like she might be having a stroke because I knew that she had not been drinking. What we learned later was that she was admitted into the hospital with symptoms of double vision, difficulty walking, talking and being cognitively impaired.

Before my sister’s harrowing experience, my family had no idea that we would be entering into the frightening world of a serious and elusive brain injury known as Autoimmune Encephalitis (AE). I write this article to help inform people about AE, but also to write my narrative as a caregiver who is still grappling with the difficulties of helping someone recovering from a brain injury. I share my experience of the initial crisis of acute care and her recovery so that others know that they are not alone feeling all of the range of thoughts and feelings that go along with supporting a person in this situation.

A Steep Learning Curve: All of a sudden we were immersed in a nightmare of which we had virtually no knowledge and a medical situation that seemed to be stumping the doctors as well. I would need to step up and accept the role known as the Medical Personal Director, along with my mother (joint role), that later transitioned into co-guardianship as my sister’s situation became complex and protracted. I was asked to consult with her medical team daily as her medical matters were marked as urgent and were changing rapidly. The decisions that we were making were life and death decisions.

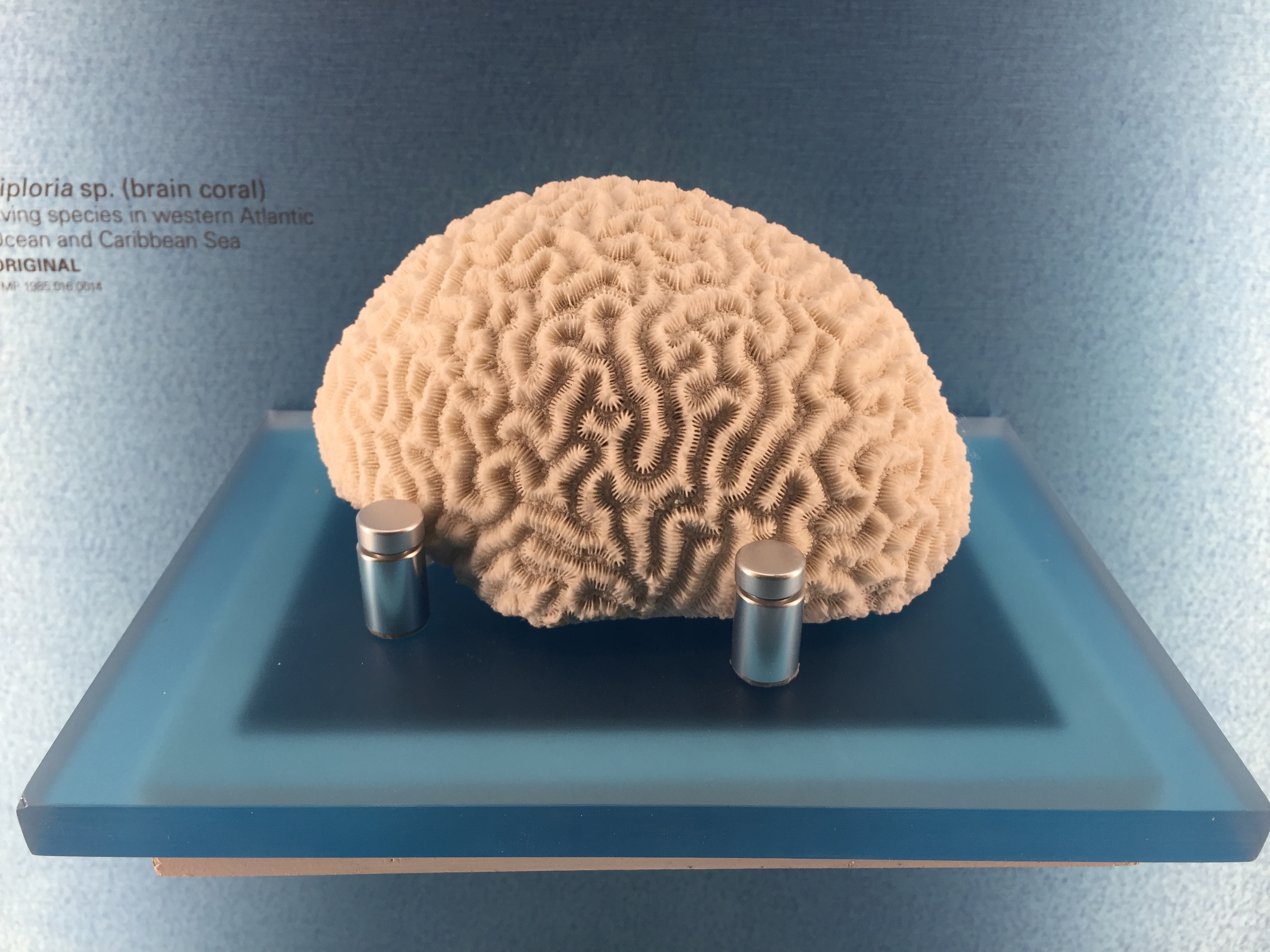

What I did not know was ahead of us was a steep learning curve about her condition which was eventually diagnosed to be AE which refers to a group of conditions that occur when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy brain cells, leading to inflammation of the brain. Interestingly, a couple of months before her situation happened, I had watched the movie Brain on Fire about a young woman named Susannah Cahalan who experienced a similar horrible journey with an autoimmune disease affecting her brain with terrible psychotic symptoms that they initially felt to be a result of addiction withdrawal, and then later believed to be other psychological disorders like Schizophrenia or Bi-polar Disorder before finding out that it was a very physical medical issue that was attacking her brain. When I watched it, I jumped to the end because I found the movie to be disturbing. I wanted to know that she would be okay and that there would be a happily ever after. Unfortunately, in my sister’s situation, there would be no quick jumping to the end of anything.

The Journey of Diagnoses: The journey of finding out what was impacting her reads more in my mind like a helix as the situation went around and around without always having clear answers as she spiralled through mental confusion and varying types of psychoses and then back again with minuscule degrees of improvement. As she was being tested and treated, she would rebound resiliently, and then relapse without much explanation. Things did not improve in a linear progression; rather, there were a series of three steps forward and two steps back in many of the stages of her recovery. Each one of her relapses went into different dark directions with varying degrees of symptoms which complicated a formal diagnosis.

The amazing South Health Campus Hospital that initially treated her in Calgary, Alberta is a teaching hospital. Therefore, we have had the mixed fortune of having a new neurological team each week of medical students, interns, residents, fellows and attending physicians (in the order of training with the attending physicians being the most trained) that have brought with them a fresh medical perspective with varying insights as to how to manage her case. However, over the long haul of three relapses of her difficult medical matter, our family has had to re-establish communication and relationships with each new neurological team each week and figure out next steps by bringing all of us up to speed about not only her care, but our perspectives about it. As her file has become thicker, there continues to be more to review and analyze for all of us.

She was then transferred to the Foothills Medical Centre Rehabilitation Unit where she was deemed ready for rehabilitation that included occupational and recreational therapy with a focus on her cognitive challenges. We were not confident that she was ready for this change given that she had just had a third relapse two weeks prior to this move; however, they were eager to transfer her to this facility because they had an opening there, and it was a difficult unit in which to be admitted.

Unfortunately, she relapsed again for a fourth time quite dramatically and her care was taken over by both the hospital psychological and neurological teams who found the entire episode quite challenging as they were not sure how to best approach it. She remained in the rehabilitation wing while this was taking place to save her place for further rehabilitation given that it had been difficult to get her into this ward. After much deliberation and advocation on our part as a family, it was determined that she would receive a course of immunoglobulin medication, and she improved again to be able to resume her rehabilitation.

Her long term care in this rehabilitation unit became complicated by her personal (family and finances); and professional matters (inability to work) which protracted the process of staying in the hospital as she awaited funding for and then a placement to an independent care facility/group home. Her medical matters were not straightforward, and required considerable attention by her transition team to consider her next steps while being in a financial and placement holding pattern.

The Initial Medical Event: She was initially admitted with some very upsetting symptoms. I have chosen to use layperson’s language to save the double read for people who have no medical background. Her eyes were physically crossed and she was seeing double. She had terrible headaches emanating from the back of her head and across the top of it and in and around her eyes. She was also describing numbness in her face and hands on one side of her body, but worse, she could no longer talk properly without slurring her words and yawning constantly. She initially complained of having memory lapses. She was unable to walk without support, and she had lost her ability to control her bodily functions for periods of time.

A young resident broke the news to us that she felt that this was some form of encephalitis, and later an MRI confirmed that the brainstem that affected all of these cognitive and motor functions was indeed inflamed. What became weirder for everyone was the fact that all of the subsequent and repeated testing which included other MRI’s, blood work, lumbar punctures, CT scans, ultrasounds, X-rays, and eventually PET scans, ruled out viruses, infection, cancer, tumours or anything that might prove as a cause for the problem in her brain. It was explained to us that there may have been an initial virus or infection that set things in motion, but it was no longer detectable.

Ongoing Medical Diagnoses: She had several emerging diagnoses as the hospital learned more about her situation:

Originally, we were told she might have Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEMS) which is a brief but intense attack of inflammation (swelling) in the brain and spinal cord and occasionally the optic nerves that damages the brain’s myelin (the white coating of nerve fibers).

Next, we were told that it might be Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) which is inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, but the intensive steroid treatment was not as immediately successful for her as it was for other CLIPPERS patients.

There was some guesswork (they were keeping an eye on it) that it might be Parenchymal Neuro-Behcet’s Syndrome (PNBS) which is a multi-system vascular-inflammatory disease of unknown origin that plays out in the brain stem, but there was not enough definitive criteria for such a diagnosis.

Autoimmune Disease (AE) became the diagnosis that now seems to cover most of her symptomatology within the definitions of also being a Central Nervous System Autoimmune condition (CNS).

When she relapsed again in the second hospital (rehabilitation ward, not a neurological ward), there was some initial confusion about how to treat her, as the psychologists who got involved determined that psychiatric matters may be the dominant matter given her various psychoses occurring even though she had a significant neurological incident precipitating all of the problems that she was experiencing psychologically. Fortunately, we and the nursing team advocated for her, and the neurologists involved gave her another course of immunoglobulin therapy to improve her autoimmune response to what was occurring in her brain, and it was successful confirming that her matters continued to be brain-based neurology issues. Otherwise, she would have been submitted to further psychiatric medication and treatment, and placed in a psychiatric ward as noted in her report. We were concerned about the considerable medication that she was taking which we had researched might have adverse interactions.

What I learned in all of this journey of AE is that there is an incredible overlap of symptoms and criteria for these rare and complex neurological diagnoses. The discreet differences have warranted ongoing testing and then, discreet adjustments to treatments. It has been a nerve-racking journey as we continue to learn about her situation one step at a time, each influencing her next steps. It was imperative that her family advocate for her as information was not always transferred accurately from hospital to hospital, and from medical team to medical team within each hospital as her file became thicker and more complicated. As a family, we were often asked questions pertaining to her file, and we felt that we were the memory keepers of her situation even though none of us had any medical background. Fortunately, my mother and I were good at taking and keeping track of her medical reports and medications.

Treatments: After reading copious amounts of peer reviewed journals about autoimmune brain matters like my sister’s situation so that I could grapple with the hospital vernacular and keep up to speed with the grim processes involved with the testing and treatment of my sister, I fell upon three layperson’s observations.

What they were uncovering about her situation is that AE and related conditions are rare, and relatively new to the field of neurology. There are more unknowns than certainties in these rare brain diagnoses in the literature. At the time of her being admitted and in the early stages, the doctors were not absolutely certain about what was happening or why this was happening to her; and as a result, they were not absolutely certain beyond a shadow of a doubt, how to treat her, although they had a range of options.

Her situation resembles a few other autoimmune diagnoses related to the brainstem and there only seemed to be very discreet differences to define one from the others.

With the label or definitions being given each auto-immune diagnosis, there appears to be only a few medical treatments that they all have in common to attempt to solve them (in various sequences and combinations, with some guesswork and trial and error at play): a) steroid treatments (intensive and maintenance amounts); b) immunoglobulin treatments; c) plasma exchange treatments; d) radiation or chemotherapy treatments (if there is cancer); e) and other autoimmune or cancer immunosuppressant medication. There are other medication options mentioned in some cases, but these have been the basic treatments listed in the literature, as well, the treatments that were all given to my sister in different orders and combinations, and in some cases, repeatedly. Fortunately, she started to make some improvements after each plasma exchange series, and especially after the third series which is also known as Plasmapheresis which is a way to ‘clean’ the blood removing antibodies from her system. After this, they have now put her on a medication known as Retuximab which requires government assistance because of its expense. It is taken every six months with ongoing review of the success of the medication.

As she stabilized after her fourth relapse, she was weaned down from her steroid medication, and other medication to stabilize her mood and affect were continued and introduced. She also had other medication that she was taking for other medical matters that had to be integrated carefully into the mix. She had many reactions to these medications: headaches, insomnia, diarrhea, vertigo, and other. It has taken considerable effort to determine what was working and what was not working and how to combine the medications with best effect.

In essence, the goal of all of her medical treatments alongside her rehabilitation therapy has been to stabilize her so that she will not relapse back into what we were seeing before as complete madness where she was unable to talk or function beyond ranting a few phrases over and over again.

Some Graphic Details: It is difficult to relay the details of the journey because they are so upsetting to remember, and there are so many of them, making the chronology of them difficult to explain. Essentially, I found her first week of the initial trauma to the brain to be where we could still communicate with her best because although she was most unable to talk, see or move, she was still very engaged with me, and she could understand and respond to what I was saying. She was still in there.

Slowly, as time progressed, her ability to walk, see and do basic things like eating or going to the bathroom improved, perhaps because these are simply tasks with some muscle memory involved. Unfortunately, her cognition regressed. At some point in the second month of being in the hospital, she was communicating like a very young child in fragment sentences at best, often in one or two word efforts that were slurred or difficult to understand.

Later, she started to experience many psychotic symptoms where she was perseverating over thoughts that would impulsively come into her mind. She was basically relaying her stream of consciousness that was in hyper-drive, likely from the steroids. She would repeat the same sentences over and over again, and we did our best to steer her away from these recurring thoughts by reading to her, listening to quiet music, or showing her pictures and photographs. Later, she started screaming and walking the hallways at night and required sedation.

There was no clear reason for why she was exhibiting these symptoms because the MRI’s were indicating that the inflammation in her brain was diminishing, but her cognition and symptoms of psychoses were not improving. She was also getting terrible headaches that required that she be in the dark and get medication for the pain. There was some concern that her eyes might be part of her problem, but the ophthalmologist ruled this out.

They were starting to be very concerned and warned us that a biopsy of the brain stem may be in order because they really did not know what else to do because she was getting worse. They consulted with two neurosurgeons. The first refused to do it given that it was a dangerous procedure with great risk to her and with no guarantee of finding anything out through this procedure. The second agreed to do it initially, but as the swelling deteriorated, the neuro-surgeon felt that it would be impossible to get anything in a biopsy sample significant enough to warrant the risky effort.

Because the plasma exchange had been successful twice before, but with almost immediate and nasty relapses, they tried it a third time, but for a longer period of time. The first and second series were each five-day courses, and the third was nine. They then put her immediately onto the Rituximab where we are now waiting to see how she will do given that it is only administered every few months. It appears that she is, as she would say to us “a work in progress”. At various times in the earlier part of her brain injury, she would say plaintively, “I am broken” which made us realize how difficult this situation must feel to her. However, her spirit was not broken as she continued to handle her circumstances with acceptance and grace. Even when she was unable to manage her thoughts, she spoke mostly of love.

Now, in the latter part of her situation, she remembers next to nothing of this above journey. It is completely lost to her. As a result, we are concerned that she may not understand the implications of her ongoing treatment and therapy. She is eager to get out of the hospital and become independent which we can fully understand; however, we are also tentative in encouraging things to happen too quickly for obvious reasons. She has had such a difficult time over the past few months, and she is still learning how to be entirely capable physically, cognitively and emotionally with what would be required of her in supervised, and then later, complete independence.

Feeling Grateful: What became very profound for me as one of her caregivers was that not only were the issues themselves very life threatening and extremely challenging, so too were some of her issues beyond her medical matters (financial and domestic). As life unfolds in complicated ways, so too does the drama lurking just beneath the surface of the calm waters until they are churned up to expose them. We learned some of her financial, social and domestic realities, and we had to navigate through them thoughtfully as they were new to us, and we were new to these situations and people involved.

Fortunately, most people were, and continue to be, profoundly generous and supportive of her. The people who I least and most expected to step up, have been amazing. Some people she/I have not seen since kindergarten, or who have moved away, travelled great distances to see her and our family. I am learning that despite her life imploding all around her, she has gotten most of her relationships right. For example, she was that person that I would call in the middle of the night when life got difficult over the years. As well, she has always worked with people from marginalized or vulnerable sectors (very young children; mentally challenged; senior citizens and other) and she is being paid back in dividends the countless hours that she has given to the people in her lifetime.

My husband and I have also learned how to ask for help which we initially found very difficult to do. It has been a very humbling process. Some people have responded graciously and some people have just been too busy. I imagine that we are not the first people to discover that being caregivers puts us face-to-face with these matters of who will and will not help. To be very clear, it has been utterly understandable why certain people have been unavailable for certain things and at different times and for very good reasons, but it is also pretty clear who did step up. We have chosen to shake off any negative feelings that we have about it and be grateful for all of the blessings in our situation because that is always the best way to feel. Here are our key blessings:

She has been in two amazing hospitals in a wonderful country that affords this type of social health care system that we all pay into in some way or another.

She has a support panel of people helping her with various parts of her difficult situation (medical, financial and domestic).

She has an incredible strength of spirit to accept and work through these difficulties.

Caregiver Fatigue: Initially, grief, shock and utter devastation took a toll on my physical body and brain. All of a sudden, the well from which I usually drew my fortitude, went dry. Exhaustion took over and the things that were normally easy for me to do became exceedingly difficult. I just stopped being interested in eating. My sleep was up and down where nightmares woke me in the wee hours of the morning and clung to me in my waking hours. Her face kept creeping into my every waking and sleeping hour.

I had to go back and forth from my home in British Columbia to Calgary, Alberta in order to help with her and my family with her medical care; and to stay on top of some of our own personal affairs that could not be put off. I found myself having a sore chest, and more aches and pains than normal. I breathed more shallowly. I forgot to drink water, or to do any of the physical activities that brought me rest, rejuvenation and pleasure before her emergency. I found myself unconsciously clenching my fists and my jaw, and carrying incredible stress into my shoulders and upper back. Whenever we got the mail, answered the phone, or had to make a decision, I agonized over what bad news might come next and my hands would shake, and I felt just a little bit dizzy. There had been so much bad news in our lives along with my sister’s situation that it was all very frightening.

As well, I was not certain what would happen when she did get well given that many of her life circumstances were also complicated. There was a very steady current of worry and fear for both my family and I about her situation. I realized that I had to get my act together or I was going to get sick and not be able to help her. I embraced the notion that the Buddhists acknowledge that “suffering is part of life”. We can plan for every eventuality, but when the dominos start tumbling over, one on top of each other, the chain of events that begin in the body can begin to distort the mind if we let it. Even though I was in a sort of shock for a day or so, I found the internal fortitude to get my footing, turn around from running away from it all, and look the situation in the eye.

The only way that I have ever learned to handle problems is to first digest them, then make a list, and then get busy with the task of getting these items done. My husband and I hunkered down and met every one of our dilemmas that involved her medical situation and started researching what we could do to be knowledgeable about it. It was also extremely important for me to be very clear with myself and other people about what I could not do. A few years ago, I would have taken on all of her medical, financial and domestic matters, but I have grown wiser, and have learned to set a few boundaries where I feel that people might be expecting more of me than I can provide. It was very overwhelming at first when people were asking and telling me what to do in every facet of my sister’s life because when a person becomes brain injured, her entire life is put on hold.

Once I was clear with myself and others about the role that I would take on with her focusing on her medical care (along with my mother), others stood up and filled the gaps. It was an amazing thing to witness. Everyone started communicating either by phone, Facebook Messenger, email and other to assess her needs and to volunteer in whatever way seemed manageable to them. Some came and brought her gifts, washed her clothes, or made sure that she was able to get out of her room on occasion. As she improved, people took her down to where she could play the piano. It became a day-by-day experience where we were learning to be cautiously optimistic.

A couple of her other family members took on the roles of joint Power of Attorney and also ran a successful Go Fund Me Campaign for the legal processes and other to establish these roles as it had been complicated to establish these roles legally. The conundrum for Tracy was that the hospital was unwilling to deem her “competent” or “incompetent” as they determined her to be “in treatment”. Unfortunately, unlike her situation in the hospital, many of her affairs could not be put on hold, and these matters became very difficult for everyone involved including her children. Many of her support networks rallied around these challenges.

Through all of it, whether we have been in Calgary or back at home in BC, my husband and I have continued to grapple with her situation by participating in conference calls, visiting with her directly or through FaceTime, completing her medical paperwork, communicating with all of her stakeholders to keep people updated, and to keep our family on track about what lies ahead as she now prepares to transition out of the hospital.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations: My life lessons in all of this have been the following and they all revolve around the continuity and communication of her care:

Patient advocacy is essential where there are matters of brain injuries. We have felt confident in the hospital care, but there have been times where our knowledge, observations and experiences with my sister have been an important piece of the puzzle for the medical team caring for her. As important as the scientific empirical data that has been developing in her file which correlate among her tests, treatments and recovery, so too has the qualitative data of our family interviews, observations and notes about her care and progress with the input of everyone visiting her (mixed data research). What has become difficult more recently as she is regaining her competence, is sustaining regular communication with the medical team. It has lagged in large part because she is no longer an acute care patient, and because my sister eagerly wants to make her own decisions. The challenge becomes determining her readiness to do so, and the value of our continued involvement in her ongoing decision-making. If we are still an important part of this process, we require ongoing communication with the key stakeholders overseeing her file.

Her continuity and communication of care from the beginning of her situation to now has been challenging. At times, with a rotating staff figuring out which treatment works for which evolving symptom. It has been an enormous puzzle that continues to be pieced together even now. Her initial round-table meetings while she was in acute care with her medical team and our family was much appreciated so that we could offer our input and ask questions. Having a good social worker at each stage of her recovery to communicate with her and us about the big picture of her life and how she will work successfully back into a new life of recovery, has been and continues to be critical. Now, it becomes important to communicate how she will transition into her next steps so that she has optimal medical care outside of the hospital with ongoing medical treatments and rehabilitation supports. As a family, we are not clear on these next steps, and I believe that we should be having these conversations so that we can anticipate these changes. Our family is not able to take her into our homes for many personal, medical and financial reasons, but we would like to be involved along with her Power of Attorneys to help her figure out what will work best for her into the future.

What would have been helpful from the beginning would have been to have more active and ongoing caregiver support. What I have learned from this situation as one of her caregivers is that I cannot do everything by myself and especially across provinces. It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes a village to care for a sick member of its community. I am reminded that she has nurtured her relationships so that now she has a good support group, but having been in the hospital this long, some of these visits from her support group are becoming fewer and further between as she improves. There has been considerable caregiver fatigue by all of us as we have rallied around her for as long as she has been in the hospital and as we grapple with the uncertainty of her developing situation. It is apparent that she will require further assistance from the transitional team to ensure that she has adequate support moving forward (new medical doctors and community resources). The communication about how things will happen so that there is less worry for the caregivers is critical in situations like my sister.

The next big questions are the following:

What happens now?

Who will be the leaders of this process and how will they communicate with all of her relevant support team?

What medical and community supports will be put into place for her?

How will she be assessed to determine her efficacy towards independence?

What is our role as her family given that we can not take her in to live with us, nor drive her to her appointments?

How will her transition be assessed for its success (accountability)?

And, the ever-present question remains: If she relapses, what then?

In my sister’s situation we have needed to be there for each other in times of trouble (family, friends, community and medical support). The communication among all of us has been and continues to be an essential part of establishing a successful future for my sister. Her autoimmune encephalitis has really opened my eyes with gratitude to the realities of brain injuries and conditions, and the amazing science that her medical team has accessed to save and rehabilitate her.